In one of the nation’s cities with the highest effective property tax rates, thousands of homeowners are covering the costs for someone else’s unused land.

A new report reveals that Baltimore undervalues its vacant lots by nearly half a billion dollars, letting absentee speculators enjoy minimal tax bills while everyday residents bear the financial load.

Roughly 13,000 homes—about 7% of the city’s housing stock—sit vacant, undermining neighborhood stability and shrinking the tax base. These lots can be assessed at 10 to 15 times less per square foot than similar occupied properties, leaving residents to pay an effective property tax rate of 2.24%, the highest in Maryland.

“When taxes on vacant lots are near zero, it becomes more profitable to sit on land than to build,” says Greg Miller, co-author of the Center for Land Economics analysis. “The city still has to raise the same revenue, so when vacant parcels are under-assessed, the shortfall lands on people who live in and improve property.”

City leaders have promised to lower tax rates below 2% and close an \$85 million budget gap. But the report points to a simpler fix—tax vacant land at its true value.

A block divided

In Baltimore’s Whittier Avenue neighborhood, a single block shows how the system has gone off track.

On one side of the street sit seven open, buildable vacant parcels; on the other, eight homes occupy nearly identical lots. They share the same zoning, road access, and development potential.

Yet the tax bills couldn’t be more different.

Texas Homeowners Could Get the Biggest Tax Cut in the State’s History—but Redistricting Fight Has Overshadowed It

The research shows that the land under those occupied homes is assessed at 10 times the value of the vacant lots next door. When compared with recent market sales, the gap widens to 15 times.

And this isn’t an isolated error. The Center’s analysis found that prime vacant land across Baltimore is consistently undervalued, even in neighborhoods with high demand.

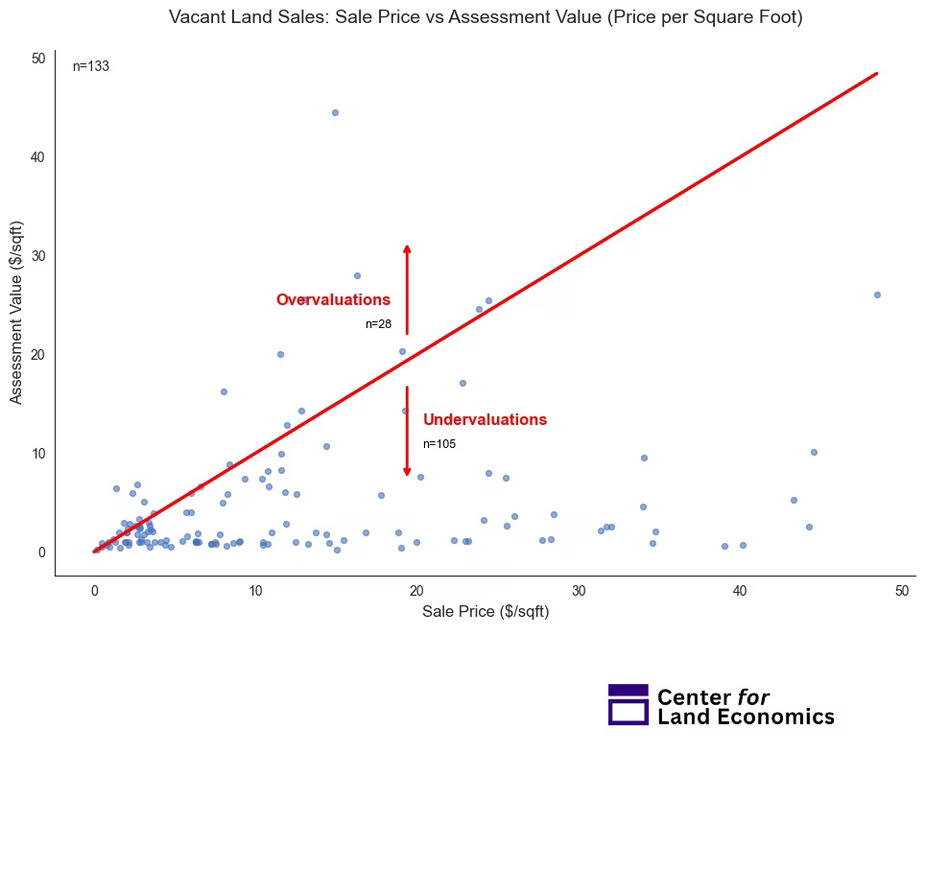

On average, lots that sold after the latest tax assessments were valued at just one-eighth of their sale price—a ratio of 8.33 to 1, when a fair market assessment would be closer to 1.0. Even before the official valuation period, the gap persisted at 2.84 to 1.

This means absentee landowners pay far less than they should, leaving homeowners and renters across the city to shoulder the difference.

How it happened and what’s changing

Maryland’s State Department of Assessments and Taxation (SDAT) often uses an allocation method, assigning land value as a percentage of a building’s assessed value based on similar properties. This practice can severely undervalue vacant lots, especially where structures have been removed, even though the land still holds development potential and market value.

That may soon change. After the Center shared its findings with local officials, SDAT committed to reassessing vacant land citywide. However, Miller warns that flaws in the agency’s data collection could hinder the effort, making truly accurate valuations difficult to achieve.

What a fix could mean for housing and development

Economists have long argued that taxing land—especially vacant land—at its true value can shift the incentives that shape cities. A more accurate system could discourage speculation, speed redevelopment, and direct growth toward areas with existing infrastructure.

This idea forms the basis of the land value tax, a model gaining renewed attention as housing shortages deepen. By taxing land based on its market potential instead of its current use, cities can motivate property owners to develop idle lots or sell to someone who will.

“Low carrying costs make it rational to hold and wait rather than develop,” Miller explains. “Correcting valuations raises the cost of keeping land idle, pushing owners to build or sell to someone who will, which results in more homes and fewer long-term vacancies.”

Cities like Pittsburgh have seen success with variations of this approach. By taxing land at higher rates than buildings and pairing it with targeted tax abatements, the city spurred redevelopment during its Renaissance II era, leading to the construction of many landmark buildings in the Golden Triangle.

Critics, however, caution that without strong data, community safeguards, and a clear rollout plan, such reforms can have unpredictable results.

Baltimore might not even need new legislation. Maryland’s current tax code already requires SDAT to assess land at market value. If the agency applied this rule consistently using recent sales data, Miller says it could promote infill housing and ease the tax burden on everyday homeowners.

What’s next for Baltimore?

Change is on the horizon. In 2026, Baltimore will begin imposing a vacancy surcharge on abandoned buildings—a tax aimed at curbing blight and pushing owners toward redevelopment.

Broader land tax reforms haven’t reached the State House yet, but momentum is growing. With housing costs rising, budget gaps widening, and clear evidence that undervalued land is costing the city millions, advocates say the current system can’t last much longer.

Whether that momentum turns into real reform remains to be seen. But for the first time in years, Baltimore may be laying the foundation for a fairer and more effective tax system.

Leave a Reply